Japanese traditional lifestyle

The History and Culture of Rice in Japan

It’s not just a staple food: food and drink made using rice play a vital part in Japan’s traditions, celebrations, and spirituality.

It is believed that rice was first brought to Japan from China via the Korean Peninsula somewhere between 300 BC and 100 BC.

Since then, rice agriculture has been a vital part of Japan’s development. Even today, the import of rice is strictly regulated in order to protect Japan’s rice agriculture industry and food security.

Food and drink made from rice play an important symbolic role in the traditions and culture of Japan.

For example, in Japanese Shintoism, rice and saké (Japanese alcohol made from rice) are commonly used as ceremonial offerings to the Shinto gods and ancestors. Saké is even sipped ceremonially as a rite at Shinto weddings.

Rice also plays an important role at celebrations in Japan. Sticky Japanese rice is often cooked with adzuki beans to make a dish called sekihan, which is commonly served at birthdays and other celebrations.

Types of Rice in Japan

The labor-intensive process of removing the bran meant that it was a luxury reserved for society’s elite. As industrialization reduced the cost of processing, the consumption of white rice began to spread throughout the population during the Meiji era (1868 – 1912).

Today, around 75% of people in Japan eat short-grain varieties of white rice, while almost 20% eat this rice mixed with other types of whole grains such as barley or millet.

There are around 300 varieties of Japanese rice grown throughout Japan today.

The most commonly grown variety is Koshihikari, a cultivar first registered in 1956. This type is known for its mild sweet flavor and pleasingly glossy look.

How Japanese People Eat Rice

As the staple of a country with such a rich food culture, the Japanese people have found countless ways to cook with rice.

Here are a few of the most common rice dishes.

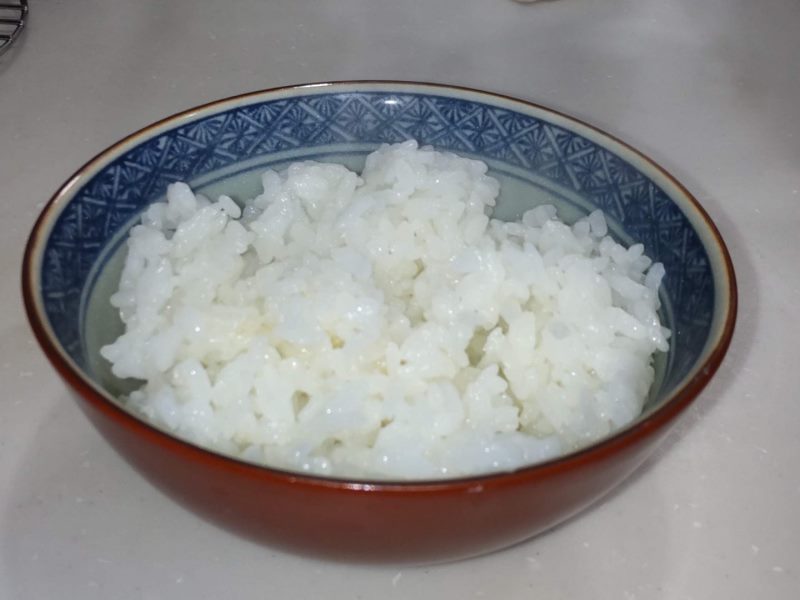

①Rice in a Traditional Japanese Meal

一汁三菜 “ichi-juu san-sai”, or “one soup, three side dishes”.

This describes a meal that includes a bowl of rice, a soup, and three side dishes; which may consist of a protein like fish or tofu, a salad (vegetables) and so on.

In this type of meal, you’ll see that rice is typically served without additional flavorings in its own bowl. Japanese people will typically eat their rice in this way to enjoy its inherent flavors.

②Sushi

③Onigiri

Commonly translated as ‘rice balls’ in English, onigiri can take a number of shapes, but the triangle style pictured here is the most common.

④Donburi

What is Miso Soup?

Miso (味噌) fermented soybean paste, is made from soybeans, grains (steamed rice or barley), salt, and koji (麹, a fermentation starter). There are many different brands and varieties of miso paste on the market.

Each miso paste and brand varies in saltiness and flavor, so adjust the amount of miso according to taste. You can also mix 2-3 types of miso together for more complex flavors. Otherwise, if you have good quality miso, enjoy its own unique characteristics.

A typical Japanese miso soup bowl holds about 200 ml of liquid. As a general rule, we add 1 tablespoon (18 g) of miso per bowl of miso soup (200 ml dashi (stock).

The most important thing you must remember is: NEVER boil miso soup once the miso has been added, otherwise it loses its flavors and aromas.

More than 80% of Japan’s annual production of miso is used in miso soup, and it is said that 75% of all Japanese people consume miso soup at least once a day.

Kamado

It means “a place for the cauldron”.

Since Japanese kamado were introduced from Korea, the word kamado itself is rooted in the Korean word gama (가마), which means a buttumak (hearth). Some kamado have dampers and draft doors for better heat control.

Together with the development of society different types of Japanese-style kamado increased. They were used for a long time until the portable cooking charcoal stove was created.

When cooking rice with a kamado, it was difficult to control the heat of the flame.

In Japanese food culture, there has been a particular revival in this Japanese-style kamado cooking among some high-end restaurants that are meticulous about their dishes.

Until the Meiji era, a kitchen was also called a kamado; there are many sayings in Japanese that use the word ‘kamado’ as it was considered a symbol of the home and the same term could even be used to mean ‘family’ or ‘household’ (similar to the word ‘hearth’ in English).

When a family member started their own branch of the family tree, it was called, ‘kamado wo wakeru,’ which means ‘to divide the stove.’

How to Split Firewood with Tools

I will show you how to make firewood by breaking it with an ax.

1. What You’ll Need

An ax (axe)

An ax (ono, yoki) is a thick heavy blade for cutting wood attached to the end of a handle that can be held with one or two hands.

A hatchet (teono, chona) is a small ax with a short handle for use in one hand (usually to chop wood.)

Some Wood

Straight-grained wood is best, avoid knots and curves if you can. The logs that you’re going to split, regardless of diameter, should be between 20 to 30 cm long. This is about the maximum size that can fit inside a kamado (fire stove)

2. Preparing to Split the Wood

Put the piece on its end, on some sort of chopping block if possible; stumps or larger pieces of wood work well. If not, just put it on the ground, propping it as needed to keep it standing. Note that driving the ax into rocky soil can dull the blade.

How to Split Wood

Splitting Wood with an Axe

Raise your splitting axe or maul above your head and let it drop. There is no need to use all your strength or a big swing!

As the axe drops, your dominant hand, – which should start with gripping the handle just beneath the axe head – should slide down to meet your other hand at the base of the axe handle.

As the axe drops, bend your knees and pull your hips back, so that your bottom sticks out; this’ll add extra kinetic energy to the swing. You’re using your hips and legs in this, and this technique is the secret to making wood splitting easy and doable for long sessions.

★SAFETY TIP

If you’re splitting a log, make sure it’s set firmly upon whatever surface you’re going to be splitting on. Otherwise, it can roll with a bad chop and even deflect the axe into your foot. That’s also why proper stance is important; keep your feet away from where you’re going to be chopping!

What do the 3 lines on one side of the ax and the 4 on the other mean?

The three and four lines represent the belief in the mountain god who watches over the work of the lumberjacks.

The three lines are ‘miki’ and represent the ‘sacred saké’ (omiki.)

The four lines on the opposite side are ‘yoki’ and represent the yoki and the shidai

The yoki are the seasonal elements that nurture trees: the sun, earth, water, and air.

The shidai are the four elements : earth, water, fire, and wind.

This is also said to be the reason why the ax is called ‘yoki’.

Before a tree is cut down, the ax is leant against it; a prayer is made to show gratitude and to ask permission for the use of tree (including the lives of other creatures) that has been given by the mountain god and to ask for safety while working.

There is also said to be a superstitious play on words that says, ‘3 (mi) wo 4(yo) keru’ meaning, ‘to evade danger.’ So even if a large tree were to fall you would be able to evade it.